In my four most recent posts, I went over the

memoirs and biographies, the

non-fiction, the

fiction and the

'classic' novels that I enjoyed reading the most in 2021. But in the very last of my 2021 roundup posts, I'll be going over some of my favourite movies. (Saying that, these are perhaps less of my 'favourite films' than the ones worth remarking on after all, nobody needs to hear that

The Godfather is a good movie.)

It's probably helpful to remark you that I took a self-directed course in film history in 2021, based around the first volume of Roger Ebert's

The Great Movies. This collection of 100-odd movie essays aims to make a tour of the landmarks of the first century of cinema, and I watched all but a handul before the year was out. I am slowly making my way through

volume two in 2022. This tome was tremendously useful, and not simply due to the background context that Ebert added to each film: it also brought me into contact with films I would have hardly come through some other means. Would I have ever discovered the sly comedy of

Trouble in Paradise (1932) or the touching proto-realism of

L'Atalante (1934) any other way? It also helped me to 'get around' to watching films I may have put off watching forever the influential

Battleship Potemkin (1925), for instance, and the

ur-epic

Lawrence of Arabia (1962) spring to mind here.

Choosing a 'worst' film is perhaps more difficult than choosing the best. There are first those that left me completely dry (

Ready or Not,

Written on the Wind, etc.), and those that were simply poorly executed. And there are those that failed to meet their own high opinions of themselves, such as the 'made for Reddit'

Tenet (2020) or the inscrutable

Vanilla Sky (2001) the latter being an almost perfect example of late-20th century cultural exhaustion.

But I must save my most severe judgement for those films where I took a visceral dislike how their subjects were portrayed. The sexually problematic

Sixteen Candles (1984) and the pseudo-Catholic vigilantism of

The Boondock Saints (1999) both spring to mind here, the latter of which combines so many things I dislike into such a short running time I'd need an entire essay to adequately express how much I disliked it.

Dogtooth (2009)

A father, a mother, a brother and two sisters live in a large and affluent house behind a very high wall and an always-locked gate. Only the father ever leaves the property, driving to the factory that he happens to own. Dogtooth goes far beyond any allusion to Josef Fritzl's cellar, though, as the children's education is a grotesque parody of home-schooling. Here, the parents deliberately teach their children the wrong meaning of words (e.g. a yellow flower is called a 'zombie'), all of which renders the outside world utterly meaningless and unreadable, and completely mystifying its very existence. It is this creepy strangeness within a 'regular' family unit in Dogtooth that is both socially and epistemically horrific, and I'll say nothing here of its sexual elements as well.

Despite its cold, inscrutable and deadpan surreality, Dogtooth invites all manner of potential interpretations. Is this film about the artificiality of the nuclear family that the West insists is the benchmark of normality? Or is it, as I prefer to believe, something more visceral altogether: an allegory for the various forms of ontological violence wrought by fascism, as well a sobering nod towards some of fascism's inherent appeals? (Perhaps it is both. In 1972, French poststructuralists Gilles and F lix Guattari wrote Anti-Oedipus, which plays with the idea of the family unit as a metaphor for the authoritarian state.) The Greek-language Dogtooth, elegantly shot, thankfully provides no easy answers.

Holy Motors (2012)

There is an infamous scene in Un Chien Andalou, the 1929 film collaboration between Luis Bu uel and famed artist Salvador Dal . A young woman is cornered in her own apartment by a threatening man, and she reaches for a tennis racquet in self-defence. But the man suddenly picks up two nearby ropes and drags into the frame two large grand pianos... each leaden with a dead donkey, a stone tablet, a pumpkin and a bewildered priest.

This bizarre sketch serves as a better introduction to Leos Carax's Holy Motors than any elementary outline of its plot, which ostensibly follows 24 hours in the life of a man who must play a number of extremely diverse roles around Paris... all for no apparent reason. (And is he even a man?) Surrealism as an art movement gets a pretty bad wrap these days, and perhaps justifiably so. But Holy Motors and Un Chien Andalou serve as a good reminder that surrealism can be, well, 'good, actually'. And if not quite high art, Holy Motors at least demonstrates that surrealism can still unnerving and hilariously funny. Indeed, recalling the whimsy of the plot to a close friend, the tears of laughter came unbidden to my eyes once again. ("And then the limousines...!")

Still, it is unclear how Holy Motors truly refreshes surrealism for the twenty-first century. Surrealism was, in part, a reaction to the mechanical and unfeeling brutality of World War I and ultimately sought to release the creative potential of the unconscious mind. Holy Motors cannot be responding to another continental conflagration, and so it appears to me to be some kind of commentary on the roles we exhibit in an era of 'post-postmodernity': a sketch on our age of performative authenticity, perhaps, or an idle doodle on the function and psychosocial function of work.

Or perhaps not. After all, this film was produced in a time that offers the near-universal availability of mind-altering substances, and this certainly changes the context in which this film was both created. And, how can I put it, was intended to be watched.

Manchester by the Sea (2016)

An absolutely devastating portrayal of a character who is unable to forgive himself and is hesitant to engage with anyone ever again. It features a near-ideal balance between portraying unrecoverable anguish and tender warmth, and is paradoxically grandiose in its subtle intimacy. The mechanics of life led me to watch this lying on a bed in a chain hotel by Heathrow Airport, and if this colourless circumstance blunted the film's emotional impact on me, I am probably thankful for it. Indeed, I find myself reduced in this review to fatuously recalling my favourite interactions instead of providing any real commentary. You could write a whole essay about one particular incident: its surfaces, subtexts and angles... all despite nothing of any substance ever being communicated. Truly stunning.

McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971)

Roger Ebert called this movie one of the saddest films I have ever seen, filled with a yearning for love and home that will not ever come. But whilst it is difficult to disagree with his sentiment, Ebert's choice of sad is somehow not quite the right word. Indeed, I've long regretted that our dictionaries don't have more nuanced blends of tragedy and sadness; perhaps the Ancient Greeks can loan us some.

Nevertheless, the plot of this film is of a gambler and a prostitute who become business partners in a new and remote mining town called Presbyterian Church. However, as their town and enterprise booms, it comes to the attention of a large mining corporation who want to bully or buy their way into the action. What makes this film stand out is not the plot itself, however, but its mood and tone the town and its inhabitants seem to be thrown together out of raw lumber, covered alternatively in mud or frozen ice, and their days (and their personalities) are both short and dark in equal measure.

As a brief aside, if you haven't seen a Roger Altman film before, this has all the trappings of being a good introduction. As Ebert went on to observe: This is not the kind of movie where the characters are introduced. They are all already here. Furthermore, we can see some of Altman's trademark conversations that overlap, a superb handling of ensemble casts, and a quietly subversive view of the tyranny of 'genre'... and the latter in a time when the appetite for revisionist portrays of the West was not very strong. All of these 'Altmanian' trademarks can be ordered in much stronger measures in his later films: in particular, his comedy-drama Nashville (1975) has 24 main characters, and my jejune interpretation of Gosford Park (2001) is that it is purposefully designed to poke fun those who take a reductionist view of 'genre', or at least on the audience's expectations. (In this case, an Edwardian-era English murder mystery in the style of Agatha Christie, but where no real murder or detection really takes place.)

On the other hand, McCabe & Mrs. Miller is actually a poor introduction to Altman. The story is told in a suitable deliberate and slow tempo, and the two stars of the film are shown thoroughly defrocked of any 'star status', in both the visual and moral dimensions. All of these traits are, however, this film's strength, adding up to a credible, fascinating and riveting portrayal of the old West.

Detour (1945)

Detour was filmed in less than a week, and it's difficult to decide out of the actors and the screenplay which is its weakest point.... Yet it still somehow seemed to drag me in.

The plot revolves around luckless Al who is hitchhiking to California. Al gets a lift from a man called Haskell who quickly falls down dead from a heart attack. Al quickly buries the body and takes Haskell's money, car and identification, believing that the police will believe Al murdered him. An unstable element is soon introduced in the guise of Vera, who, through a set of coincidences that stretches credulity, knows that this 'new' Haskell (ie. Al pretending to be him) is not who he seems. Vera then attaches herself to Al in order to blackmail him, and the world starts to spin out of his control.

It must be understood that none of this is executed very well. Rather, what makes Detour so interesting to watch is that its 'errors' lend a distinctively creepy and unnatural hue to the film. Indeed, in the early twentieth century, Sigmund Freud used the word unheimlich to describe the experience of something that is not simply mysterious, but something creepy in a strangely familiar way. This is almost the perfect description of watching Detour its eerie nature means that we are not only frequently second-guessed about where the film is going, but are often uncertain whether we are watching the usual objective perspective offered by cinema.

In particular, are all the ham-fisted segues, stilted dialogue and inscrutable character motivations actually a product of Al inventing a story for the viewer? Did he murder Haskell after all, despite the film 'showing' us that Haskell died of natural causes? In other words, are we watching what Al wants us to believe? Regardless of the answers to these questions, the film succeeds precisely because of its accidental or inadvertent choices, so it is an implicit reminder that seeking the director's original intention in any piece of art is a complete mirage. Detour is certainly not a good film, but it just might be a great one. (It is a short film too, and, out of copyright, it is available online for free.)

Safe (1995)

Safe is a subtly disturbing film about an upper-middle-class housewife who begins to complain about vague symptoms of illness. Initially claiming that she doesn't feel right, Carol starts to have unexplained headaches, a dry cough and nosebleeds, and eventually begins to have trouble breathing. Carol's family doctor treats her concerns with little care, and suggests to her husband that she sees a psychiatrist.

Yet Carol's episodes soon escalate. For example, as a 'homemaker' and with nothing else to occupy her, Carol's orders a new couch for a party. But when the store delivers the wrong one (although it is not altogether clear that they did), Carol has a near breakdown. Unsure where to turn, an 'allergist' tells Carol she has "Environmental Illness," and so Carol eventually checks herself into a new-age commune filled with alternative therapies.

On the surface, Safe is thus a film about the increasing about of pesticides and chemicals in our lives, something that was clearly felt far more viscerally in the 1990s. But it is also a film about how lack of genuine healthcare for women must be seen as a critical factor in the rise of crank medicine. (Indeed, it made for something of an uncomfortable watch during the coronavirus lockdown.) More interestingly, however, Safe gently-yet-critically examines the psychosocial causes that may be aggravating Carol's illnesses, including her vacant marriage, her hollow friends and the 'empty calorie' stimulus of suburbia. None of this should be especially new to anyone: the gendered Victorian term 'hysterical' is often all but spoken throughout this film, and perhaps from the very invention of modern medicine, women's symptoms have often regularly minimised or outright dismissed. (Hilary Mantel's 2003 memoir, Giving Up the Ghost is especially harrowing on this.)

As I opened this review, the film is subtle in its messaging. Just to take one example from many, the sound of the cars is always just a fraction too loud: there's a scene where a group is eating dinner with a road in the background, and the total effect can be seen as representing the toxic fumes of modernity invading our social lives and health. I won't spoiler the conclusion of this quietly devasting film, but don't expect a happy ending.

The Driver (1978)

Critics grossly misunderstood The Driver when it was first released. They interpreted the cold and unemotional affect of the characters with the lack of developmental depth, instead of representing their dissociation from the society around them. This reading was encouraged by the fact that the principal actors aren't given real names and are instead known simply by their archetypes instead: 'The Driver', 'The Detective', 'The Player' and so on. This sort of quasi-Jungian erudition is common in many crime films today (Reservoir Dogs, Kill Bill, Layer Cake, Fight Club), so the critics' misconceptions were entirely reasonable in 1978.

The plot of The Driver involves the eponymous Driver, a noted getaway driver for robberies in Los Angeles. His exceptional talent has far prevented him from being captured thus far, so the Detective attempts to catch the Driver by pardoning another gang if they help convict the Driver via a set-up robbery. To give himself an edge, however, The Driver seeks help from the femme fatale 'Player' in order to mislead the Detective.

If this all sounds eerily familiar, you would not be far wrong. The film was essentially remade by Nicolas Winding Refn as Drive (2011) and in Edgar Wright's 2017 Baby Driver. Yet The Driver offers something that these neon-noir variants do not. In particular, the car chases around Los Angeles are some of the most captivating I've seen: they aren't thrilling in the sense of tyre squeals, explosions and flying boxes, but rather the vehicles come across like wild animals hunting one another. This feels especially so when the police are hunting The Driver, which feels less like a low-stakes game of cat and mouse than a pack of feral animals working together a gang who will tear apart their prey if they find him. In contrast to the undercar neon glow of the Fast & Furious franchise, the urban realism backdrop of the The Driver's LA metropolis contributes to a sincere feeling of artistic fidelity as well.

To be sure, most of this is present in the truly-excellent Drive, where the chase scenes do really communicate a credible sense of stakes. But the substitution of The Driver's grit with Drive's soft neon tilts it slightly towards that common affliction of crime movies: style over substance. Nevertheless, I can highly recommend watching The Driver and Drive together, as it can tell you a lot about the disconnected socioeconomic practices of the 1980s compared to the 2010s. More than that, however, the pseudo-1980s synthwave soundtrack of Drive captures something crucial to analysing the world of today. In particular, these 'sounds from the past filtered through the present' bring to mind the increasing role of nostalgia for lost futures in the culture of today, where temporality and pop culture references are almost-exclusively citational and commemorational.

The Souvenir (2019)

The ostensible outline of this quietly understated film follows a shy but ambitious film student who falls into an emotionally fraught relationship with a charismatic but untrustworthy older man. But that doesn't quite cover the plot at all, for not only is The Souvenir a film about a young artist who is inspired, derailed and ultimately strengthened by a toxic relationship, it is also partly a coming-of-age drama, a subtle portrait of class and, finally, a film about the making of a film.

Still, one of the geniuses of this truly heartbreaking movie is that none of these many elements crowds out the other. It never, ever feels rushed. Indeed, there are many scenes where the camera simply 'sits there' and quietly observes what is going on. Other films might smother themselves through references to 18th-century oil paintings, but The Souvenir somehow evades this too. And there's a certain ring of credibility to the story as well, no doubt in part due to the fact it is based on director Joanna Hogg's own experiences at film school. A beautifully observed and multi-layered film; I'll be happy if the sequel is one-half as good.

The Wrestler (2008)

Randy 'The Ram' Robinson is long past his prime, but he is still rarin' to go in the local pro-wrestling circuit. Yet after a brutal beating that seriously threatens his health, Randy hangs up his tights and pursues a serious relationship... and even tries to reconnect with his estranged daughter. But Randy can't resist the lure of the ring, and readies himself for a comeback.

The stage is thus set for Darren Aronofsky's The Wrestler, which is essentially about what drives Randy back to the ring. To be sure, Randy derives much of his money from wrestling as well as his 'fitness', self-image, self-esteem and self-worth. Oh, it's no use insisting that wrestling is fake, for the sport is, needless to say, Randy's identity; it's not for nothing that this film is called The Wrestler.

In a number of ways, The Sound of Metal (2019) is both a reaction to (and a quiet remake of) The Wrestler, if only because both movies utilise 'cool' professions to explore such questions of identity. But perhaps simply when The Wrestler was produced makes it the superior film. Indeed, the role of time feels very important for the Wrestler. In the first instance, time is clearly taking its toll on Randy's body, but I felt it more strongly in the sense this was very much a pre-2008 film, released on the cliff-edge of the global financial crisis, and the concomitant precarity of the 2010s.

Indeed, it is curious to consider that you couldn't make The Wrestler today, although not because the relationship to work has changed in any fundamentalway. (Indeed, isn't it somewhat depressing the realise that, since the start of the pandemic and the 'work from home' trend to one side, we now require even more people to wreck their bodies and mental health to cover their bills?) No, what I mean to say here is that, post-2016, you cannot portray wrestling on-screen without, how can I put it, unwelcome connotations. All of which then reminds me of Minari's notorious red hat...

But I digress. The Wrestler is a grittily stark darkly humorous look into the life of a desperate man and a sorrowful world, all through one tragic profession.

Thief (1981)

Frank is an expert professional safecracker and specialises in high-profile diamond heists. He plans to use his ill-gotten gains to retire from crime and build a life for himself with a wife and kids, so he signs on with a top gangster for one last big score. This, of course, could be the plot to any number of heist movies, but Thief does something different. Similar to The Wrestler and The Driver (see above) and a number of other films that I watched this year, Thief seems to be saying about our relationship to work and family in modernity and postmodernity.

Indeed, the 'heist film', we are told, is an understudied genre, but part of the pleasure of watching these films is said to arise from how they portray our desired relationship to work. In particular, Frank's desire to pull off that last big job feels less about the money it would bring him, but a displacement from (or proxy for) fulfilling some deep-down desire to have a family or indeed any relationship at all. Because in theory, of course, Frank could enter into a fulfilling long-term relationship right away, without stealing millions of dollars in diamonds... but that's kinda the entire point: Frank needing just one more theft is an excuse to not pursue a relationship and put it off indefinitely in favour of 'work'. (And being Federal crimes, it also means Frank cannot put down meaningful roots in a community.) All this is communicated extremely subtly in the justly-lauded lowkey diner scene, by far the best scene in the movie.

The visual aesthetic of Thief is as if you set The Warriors (1979) in a similarly-filthy Chicago, with the Xenophon-inspired plot of The Warriors replaced with an almost deliberate lack of plot development... and the allure of The Warriors' fantastical criminal gangs (with their alluringly well-defined social identities) substituted by a bunch of amoral individuals with no solidarity beyond the immediate moment. A tale of our time, perhaps.

I should warn you that the ending of Thief is famously weak, but this is a gritty, intelligent and strangely credible heist movie before you get there.

Uncut Gems (2019)

The most exhausting film I've seen in years; the cinematic equivalent of four cups of double espresso, I didn't even bother even trying to sleep after downing Uncut Gems late one night. Directed by the two Safdie Brothers, it often felt like I was watching two films that had been made at the same time. (Or do I mean two films at 2X speed?)

No, whatever clumsy metaphor you choose to adopt, the unavoidable effect of this film's finely-tuned chaos is an uncompromising and anxiety-inducing piece of cinema. The plot follows Howard as a man lost to his countless vices mostly gambling with a significant side hustle in adultery, but you get the distinct impression he would be happy with anything that will give him another high. A true junkie's junkie, you might say. You know right from the beginning it's going to end in some kind of disaster, the only question remaining is precisely how and what.

Portrayed by an (almost unrecognisable) Adam Sandler, there's an uncanny sense of distance in the emotional chasm between 'Sandler-as-junkie' and 'Sandler-as-regular-star-of-goofy-comedies'. Yet instead of being distracting and reducing the film's affect, this possibly-deliberate intertextuality somehow adds to the masterfully-controlled mayhem. My heart races just at the memory. Oof.

Woman in the Dunes (1964)

I ended up watching three films that feature sand this year: Denis Villeneuve's Dune (2021), Lawrence of Arabia (1962) and Woman in the Dunes. But it is this last 1964 film by Hiroshi Teshigahara that will stick in my mind in the years to come. Sure, there is none of the Medician intrigue of Dune or the Super Panavision-70 of Lawrence of Arabia (or its quasi-orientalist score, itself likely stolen from Anton Bruckner's 6th Symphony), but Woman in the Dunes doesn't have to assert its confidence so boldly, and it reveals the enormity of its plot slowly and deliberately instead. Woman in the Dunes never rushes to get to the film's central dilemma, and it uncovers its terror in little hints and insights, all whilst establishing the daily rhythm of life.

Woman in the Dunes has something of the uncanny horror as Dogtooth (see above), as well as its broad range of potential interpretations. Both films permit a wide array of readings, without resorting to being deliberately obscurantist or being just plain random it is perhaps this reason why I enjoyed them so much. It is true that asking 'So what does the sand mean?' sounds tediously sophomoric shorn of any context, but it somehow applies to this thoughtfully self-contained piece of cinema.

A Quiet Place (2018)

Although A Quiet Place was not actually one of the best films I saw this year, I'm including it here as it is certainly one of the better 'mainstream' Hollywood franchises I came across. Not only is the film very ably constructed and engages on a visceral level, I should point out that it is rare that I can empathise with the peril of conventional horror movies (and perhaps prefer to focus on its cultural and political aesthetics), but I did here.

The conceit of this particular post-apocalyptic world is that a family is forced to live in almost complete silence while hiding from creatures that hunt by sound alone. Still, A Quiet Place engages on an intellectual level too, and this probably works in tandem with the pure 'horrorific' elements and make it stick into your mind. In particular, and to my mind at least, A Quiet Place a deeply American conservative film below the surface: it exalts the family structure and a certain kind of sacrifice for your family. (The music often had a passacaglia-like strain too, forming a tombeau for America.) Moreover, you survive in this dystopia by staying quiet that is to say, by staying stoic suggesting that in the wake of any conflict that might beset the world, the best thing to do is to keep quiet. Even communicating with your loved ones can be deadly to both of you, so not emote, acquiesce quietly to your fate, and don't, whatever you do, speak up. (Or join a union.)

I could go on, but The Quiet Place is more than this. It's taut and brief, and despite cinema being an increasingly visual medium, it encourages its audience to develop a new relationship with sound.

I've written about bearer tokens and how much pain they cause me before, but sadly wishing for a better world doesn't make it happen so I'm making do with what's available. Okta has a feature called Device Trust which allows to you configure access control policies that prevent people obtaining tokens unless they're using a trusted device. This doesn't actually bind the tokens to the hardware in any way, so if a device is compromised or if a user is untrustworthy this doesn't prevent the token ending up on an unmonitored system with no security policies. But it's an incremental improvement, other than the fact that for desktop it's only supported on Windows and MacOS, which really doesn't line up well with my interests.

I've written about bearer tokens and how much pain they cause me before, but sadly wishing for a better world doesn't make it happen so I'm making do with what's available. Okta has a feature called Device Trust which allows to you configure access control policies that prevent people obtaining tokens unless they're using a trusted device. This doesn't actually bind the tokens to the hardware in any way, so if a device is compromised or if a user is untrustworthy this doesn't prevent the token ending up on an unmonitored system with no security policies. But it's an incremental improvement, other than the fact that for desktop it's only supported on Windows and MacOS, which really doesn't line up well with my interests. In my three most recent posts, I went over the

In my three most recent posts, I went over the  More ICFP-inspired experiments using the

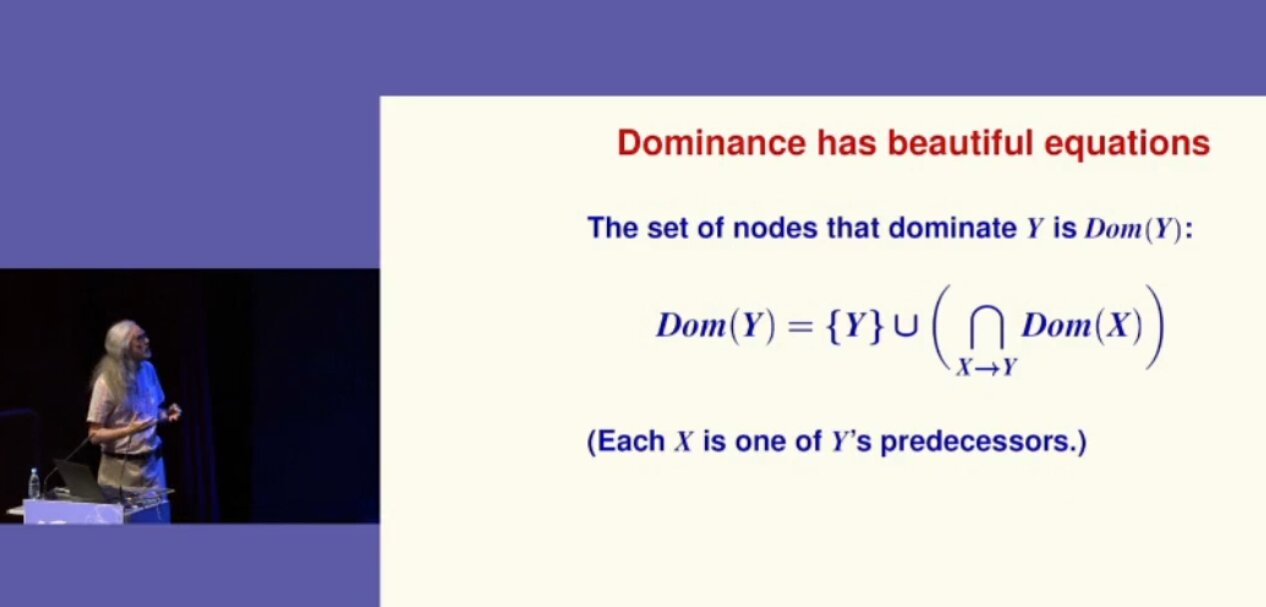

More ICFP-inspired experiments using the  Norman Ramsey shows a formula

Norman Ramsey shows a formula

The IDE

The IDE

A chatbot

A chatbot

The Python programming language is one of the most popular and in huge demand. It is free, has a large community, is intended for the development of projects of varying complexity, is easy to learn, and opens up great opportunities for programmers. To work comfortably with it, you need special Python tools, which are able to simplify your work. We have selected the best Python tools that will be relevant in 2021.

The Python programming language is one of the most popular and in huge demand. It is free, has a large community, is intended for the development of projects of varying complexity, is easy to learn, and opens up great opportunities for programmers. To work comfortably with it, you need special Python tools, which are able to simplify your work. We have selected the best Python tools that will be relevant in 2021.